Motivation Matters: Why Parents Need Science, Not Just Instinct

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” — Aristotle

Parenting today often feels like a balancing act between quick fixes and long-term goals. It’s tempting to reach for bribes, punishments, or praise to get through the daily grind — and in the moment, they work. But as psychology and neuroscience show, what secures compliance today can quietly erode curiosity, resilience, and the joy of learning tomorrow.

This series explores the science of motivation in children: why rewards can backfire, when they can be used wisely, how praise can build (or undermine) agency, and how resilience and mastery grow in the “just-right” challenges of development. Drawing on research from Deci and Ryan’s Self-Determination Theory, Carol Dweck’s work on Growth Mindset, Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development, and insights from neuroscience on dopamine and flow, we’ll move beyond parenting on autopilot to a framework grounded in evidence.

My aim is not to prescribe rigid rules, but to offer parents and educators a roadmap for nurturing motivation that lasts — one built not on shortcuts, but on curiosity, autonomy, and the deep satisfaction of master. And again, do note that I am a layman - my observations are based on my own reading, research and my first hand experience of working in early years education these past 10 years or so. So if you are an expert, please do shout out when I misinterpret the data and what I should be reading!

Key Points

Motivation is not just about behaviour — it is wired into children’s brains through dopamine and reward pathways.

Intrinsic motivation (curiosity, mastery, play) is more powerful and sustainable than extrinsic motivation (rewards, bribes, praise).

Overuse of rewards can undermine a child’s natural joy in learning, recalibrating the brain to expect payoffs.

The science shows that autonomy, mastery, and connection are the building blocks of lasting motivation.

Parenting on instinct often defaults to expediency; science offers a more sustainable roadmap.

Parenting on Autopilot

It is 7 p.m. The dinner plates are still on the table, the dishwasher needs stacking, emails are pinging from work, and your child is dragging their feet about homework. You promise: “If you do your Mathletics you can have a treat.” The sums get done. Problem solved. Or is it?

This scenario is familiar to many parents — high-performing professionals who are often stretched thin and looking for effective shortcuts. It feels rational: use a simple carrot to get the job done. But what if this strategy quietly erodes the very quality we want most for our children: the ability to motivate themselves without needing a bribe?

Developmental psychologists and cognitive neuroscientists warn us that what seems expedient in the moment can be costly in the long run. As Edward Deci, co-founder of Self-Determination Theory, has cautioned:

“When people are rewarded for doing something, they sometimes lose interest in the activity itself.”

This is not just a behavioural quirk; it is a measurable shift in how the brain responds to effort and reward.

The Hidden Architecture of Motivation

Motivation is not a “soft skill.” It is grounded in neurobiology. At its core is dopamine, a neuromodulator and transmitter that fuels our desire to act. Dopamine does not simply make us feel good; it signals anticipation — the expectation that effort will lead to something rewarding. It motivates us to try, persist, and overcome obstacles.

For children, this means the brain naturally rewards curiosity and mastery. When a child solves a puzzle, builds a tower, or reads a new word, dopamine surges in the striatum and prefrontal cortex — areas linked to learning and memory (Murayama et al., Neuron, 2010). The activity itself becomes rewarding. This is intrinsic motivation: doing something for the sheer joy of it

But dopamine is also triggered by external rewards — sweets, stickers, praise. These work too, but with a catch. If the brain learns to associate the reward with the activity, the natural dopamine release tied to the activity itself can diminish. Over time, the child comes to do the puzzle or homework not for joy, but for the sticker or praise (Lepper, Stanford 2003).. Without the external cue, the motivation fades. This is the neuroscience behind what psychologists call the overjustification effect.

Why Expediency Backfires

The high-achieving parent’s dilemma is that expedient strategies are seductive. They deliver compliance quickly in a time-poor household. Yet research repeatedly shows their unintended consequences.

In the classic Lepper, Greene, and Nisbett (1973) study, children who loved drawing were divided into three groups: one promised a reward, one given an unexpected reward, and one with no reward. Weeks later, those promised a reward showed less interest in drawing than before. Their natural curiosity had been crowded out.

Deci, Koestner, and Ryan’s (1999) meta-analysis of over 100 experiments confirmed this pattern: tangible rewards like money or toys reliably reduced intrinsic motivation, particularly for tasks children initially enjoyed. The very behaviours we want to strengthen are weakened.

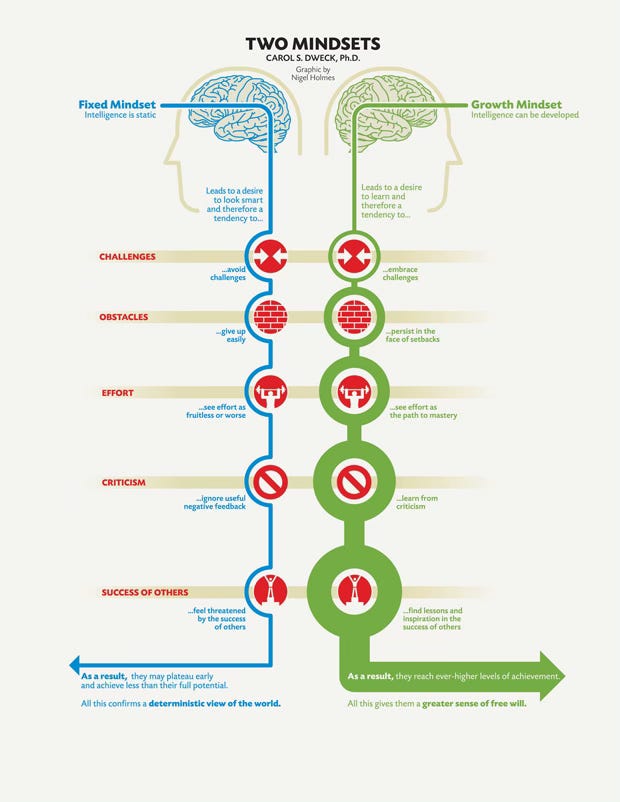

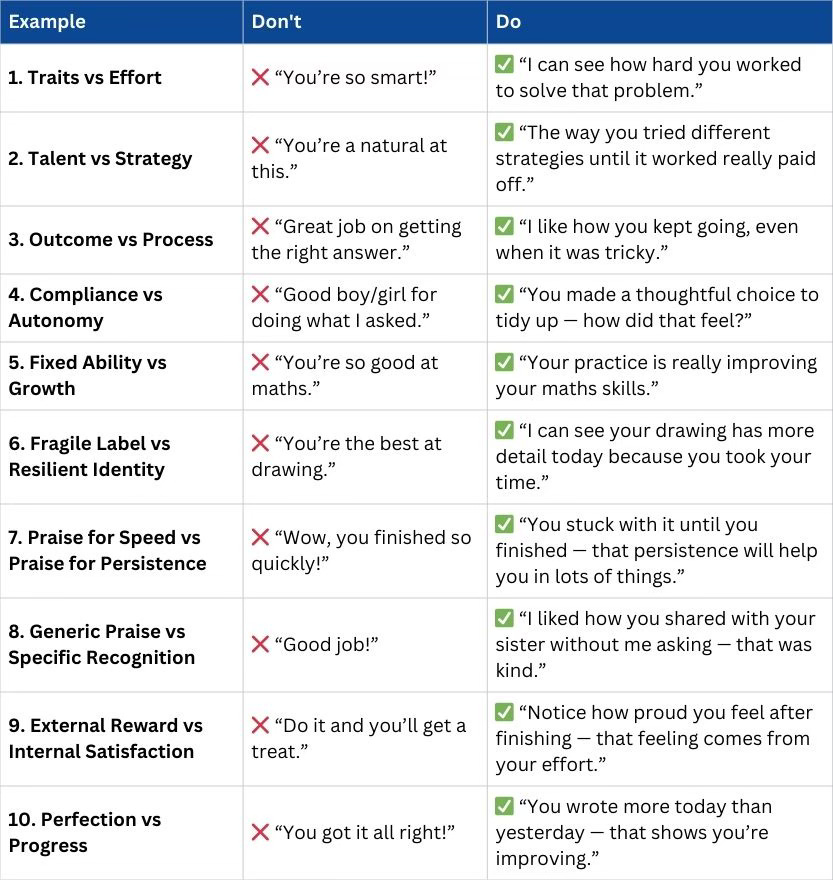

Carol Dweck’s research on mindset (1998; 2006) showed how even praise, when focused on traits (“You’re smart”), can make children more risk-averse and less resilient. By contrast, praising effort builds persistence and a willingness to take on challenges.

Conventional wisdom — reward the behaviour you want — feels logical. Cognitive science reveals it is shortsighted.

Why Intrinsic Motivation Matters More

Why labour this point? Because intrinsic motivation is not a luxury — it is the foundation of resilience, adaptability, and lifelong success. A child driven by curiosity rather than compliance is more likely to:

Persist through difficulty. Dopamine firing during effort reinforces persistence (Schultz, 2016).

Enter flow states. Csíkszentmihályi (1990) described flow as deep absorption in a challenging task; it is intrinsically rewarding and linked to creativity.

Achieve academically and emotionally. Ryan & Deci (2000) found intrinsic motivation correlated with higher achievement and well-being.

The child who reads because they want to, builds Lego because it is fun, or tackles a maths puzzle because it is challenging, is laying down neural and psychological foundations that will carry into adulthood.

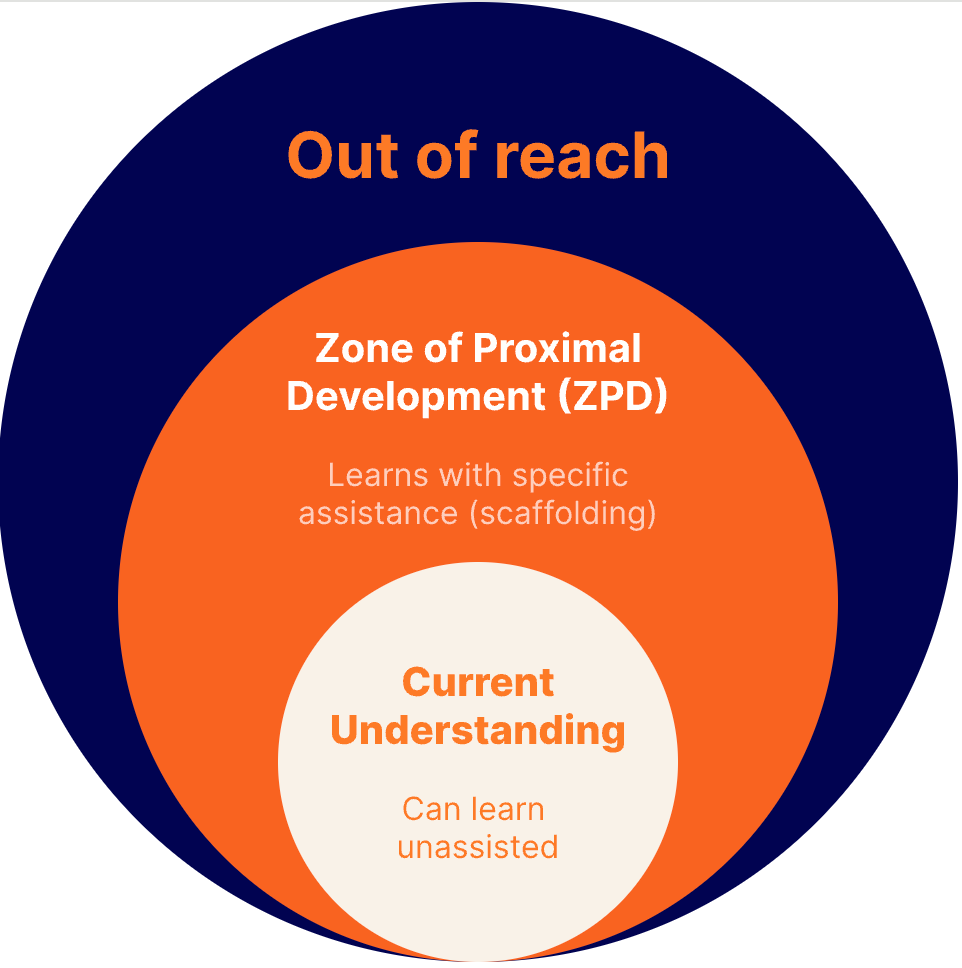

The Zone of Proximal Development: Where Motivation Thrives

Lev Vygotsky’s concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) offers a way forward. The ZPD is the sweet spot between what a child can do alone and what they can do with guidance. In this zone, tasks are difficult enough to stretch but not so difficult as to overwhelm.

Within the ZPD, motivation flourishes. Success feels earned, mastery is tangible, and dopamine rewards each small step. The adult’s role is to provide scaffolding — hints, prompts, encouragement — without taking over, being mindful as we should be of the language we employ to nurture persistence (effort over outcome). Over time, the scaffolding is removed, and the child internalises both the skill and the belief: “I can do hard things.” This is the antidote to stickers and bribes: creating environments where children experience the natural rewards of mastery, not the artificial pull of external prizes.

Replacing Shortcuts with Science

Parents do not need to abandon all tools. Rather, we need to align them with what the science says sustains motivation:

Use extrinsic rewards sparingly and temporarily — as scaffolds for unappealing but necessary routines (tooth brushing, safety compliance). Then fade them out.

Praise effort, strategy, and persistence, not innate traits. Make praise informational rather than controlling.

Offer meaningful choices. Neuroscience shows that even small choices activate reward circuits and foster autonomy (Leotti & Delgado, 2011).

Set “just right” challenges in the ZPD. Too easy is boring; too hard is demotivating. The sweet spot builds resilience.

Model motivation yourself. Show your children how you persist, learn, and grow.

Reflection for Parents

Take a moment to ask:

Where am I relying on bribes or rewards as shortcuts?

How does my child respond when the prize is absent?

Which activities light up my child’s curiosity without external prompting?

As Ryan & Deci (2000) remind us:

“Intrinsic motivation is fragile, yet it is the fuel of deep learning and creativity.”

Our job as parents is not to extinguish that flame with expedient tricks, but to feed it with environments where curiosity, mastery, and joy can thrive.

A framework

I’ll be building some printable assets that parents can download to stick up around the house as a visual aid to help rephrase the defaults we have in us based on some of this thinking. Until then, I hope the below table will help…

A final thought for us to keep in our minds: whenever I want to praise, I’ll ask myself:

“Am I focusing on effort, strategy, or choice? If not, I’ll rephrase.”

Looking Ahead

This blog sets the stage for a series on the science of motivation in children. Each essay will explore one dimension of this puzzle: why rewards backfire, when they work, how praise can build agency, how resilience grows in the Zone of Proximal Development, the neuroscience of mastery, and why conventional wisdom often misleads. Together, they will offer a framework for busy parents who want to move beyond shortcuts toward evidence-based strategies that build lifelong motivation.

In the next instalment, we will explore why rewards so often backfire at the level of brain chemistry — and how to avoid teaching your child that joy itself is not enough.

References for Further Reading

Deci, E.L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R.M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 627–668.

Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

Murayama, K. et al. (2010). From external regulation to self-regulation: Neural basis of the shift from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation. Neuron, 68(4), 703–717.

Dweck, C.S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Lepper, M.R., Greene, D., & Nisbett, R.E. (1973). Undermining children’s intrinsic interest with extrinsic reward: A test of the overjustification hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28(1), 129–137.

Leotti, L.A. & Delgado, M.R. (2011). The inherent reward of choice. PNAS, 108(30), 13823–13828.

Schultz, W. (2016). Dopamine reward prediction error coding. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 18(1), 23–32.