I’ve long been interested in psychology. In fact, when mulling over my degree choices on my UCAS application form all those years ago, my choices were Modern Chinese Studies, for the Universities that scraped an entry into taught the subject back then (not many), and Psychology, for those that didn’t. I suppose what linked both was my interest in people and how they use language to frame their understanding of the world and their place within it.

I was lucky enough to have two amazing teachers when studying for my A Levels. Mr Murphy, who taught English Language, and Mr Wayman, a vivacious young pup of a 24 yr old teacher, fresh out of Oxbridge to bring literature to oiks like me. As passionate as Mr Wayman was, and as magical as he made literature to be, it was Mr Murphy’s history of the English language and his introduction to socio-linguistics and the philosophy of language that really stuck with me.

It was through that introduction that I got into Chomsky, and through Chomsky to Edward Said, and his immense tome, Orientalism, which, outside of my GCSE in Japanese, really steered my interest towards East Asia and China in particular. I was fascinated by the concept of the “Other” and how we still fall prey to the tribalism that it suggests is inherent in us even today. It was very much one of the reasons why I set up bilingual schools in Hatching Dragons - to see whether or not through language we can learn to overcome such in-built bias and bigotry.

And in all of this, I suppose I’ve been searching for an answer to the questions on the nature of us humans. What makes us so fearful of the other? So desperate to be right? What makes us so ashamed of being wrong? What makes us so desperate to be seen and heard? What makes us deny what is true? What makes us all so happy? And so sad? And what makes us strive to survive and fight, every day, to make it work?

Explosion in Mental Health Problems

I reminisce principally because of the recent coverage of the Health Secretary, Wes Streeting’s, recent briefings on the “over-diagnosis” of mental health issues. Here he is on the Laura Kuennsberg breakfast show talking on the issue..

It very much appears to be another lever for the Government’s overall strategy to reduce the welfare bill and drive people back into work. But leaving aside the rather reductive and binary arguments on whether those people are “benefits cheats” or in genuine need, I think it’s probably first quite important to accept that this debate is by no means new. Here is the full video of the Intelligence2 Debate, entitled “Psychiatrists and the pharma industry are to blame for the current ‘epidemic’ of mental disorders”. It was recorded in 2014.

It makes for compelling viewing in light of the recent debate as much of what was discussed then is true now. The debate focusses in and around quite philosophical arguments about what it means to be a human, and whether or not the struggles that we face, contend with an overcome are indeed part of what makes us human. That is very much the perspective of Will Self, who contends:

“it’s not the chemical imbalance in the brain that should concern us, but the moral imbalance in the society that expects happiness to be perpetual, and sadness to be a pathology.”

Have we just become incapable of dealing with difficulty? Do we spend too much time scrolling through the perfectly confected lives of online influencers to compare what little we have with what surfeit they enjoy?

Or have we rightly moved towards the medicalisation of emotion, treating the negatives as a malaise that can be doped out of ones construct or consciousness - an immunisation from pain or grief. Does the explosion in diagnoses and proscriptions for anti-depressants suggest, as Dr Simon Wesseley of Kings (at least in that debate), Dr Lucy Foulkes, and Dr Stephen Hinshaw do, that such a growth is to be welcomed as signs of a culture that is becoming increasingly emotionally aware, not necessarily “more ill”. As Dr Foulkes puts it

“Increased reporting doesn't necessarily mean more illness — it might mean more honesty.”

After all, previous generations may well have just suffered in silence and we might finally be moving towards a more awakened emotional reality, where the full spectrum of ones emotional reality - both the positive and negative - are as valid as reason, and to be acted upon and realised in full, irrespective of the cost to you and yours. Does suppression only lead to misery or not?

Growth of Diagnostic Categories

What is certainly true is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has had multiple iterations over the years, reaching a peak of 297 disorders in 1994 (from the original 106 in the first volume published in 1952) to then return to 157 in the fifth edition published in 2022.

On paper, that sounds like good news. But even though fewer total categories exist, the broadening of criteria within umbrella diagnoses means more people can fall within a given disorder (e.g., ADHD, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Generalised Anxiety Disorder). This is why critics argue that medicalisation may have expanded despite the category reduction. For instance, Autism Spectrum Disorder is now the catch-all for previously separate diagnostic categories of Autistic Disorder; Asperger’s Syndrome; Childhood Disintegrative Disorder; and PDD-NOS (previously separate in DSM-IV), and with wider diagnostic parameters, more people can be (in)correctly diagnosed subject to the assessment of the clinician (autism diagnoses in the UK have risen by 787% between 1998 and 2018). So it’s time to look at some pretty depressing statistics and death by charts….

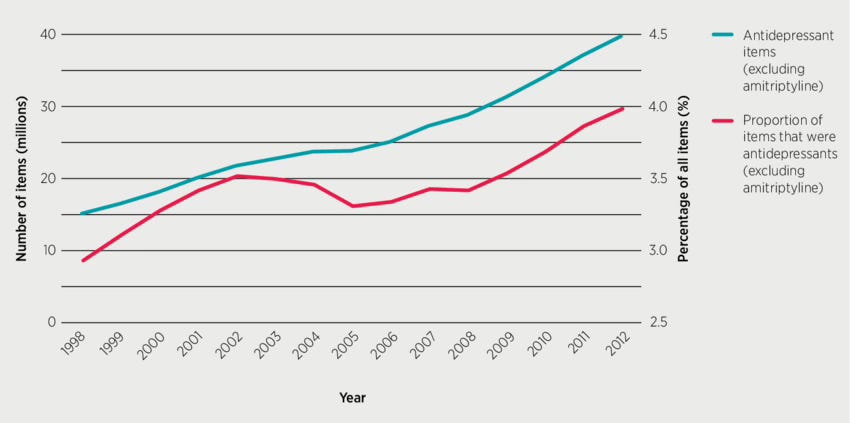

Last year, the NHS reported that a record 8.7 million people were being prescribed antidepressants, which accounts for around 15 % of the population. I found this interesting report on Researchgate from 2014, which cites data from 1998 to 2012 (over 10 years ago). The trend line is clear as much as it is stark

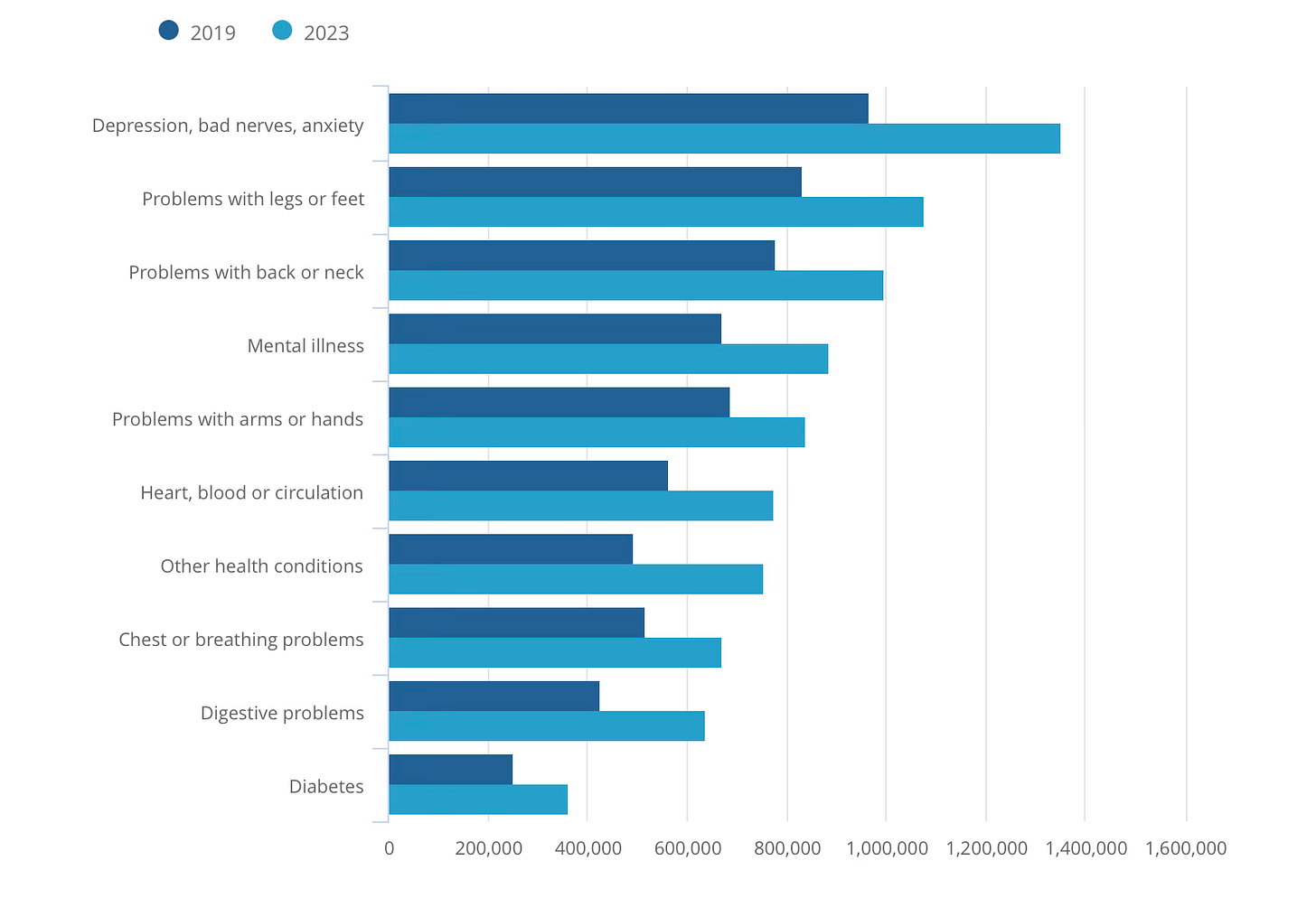

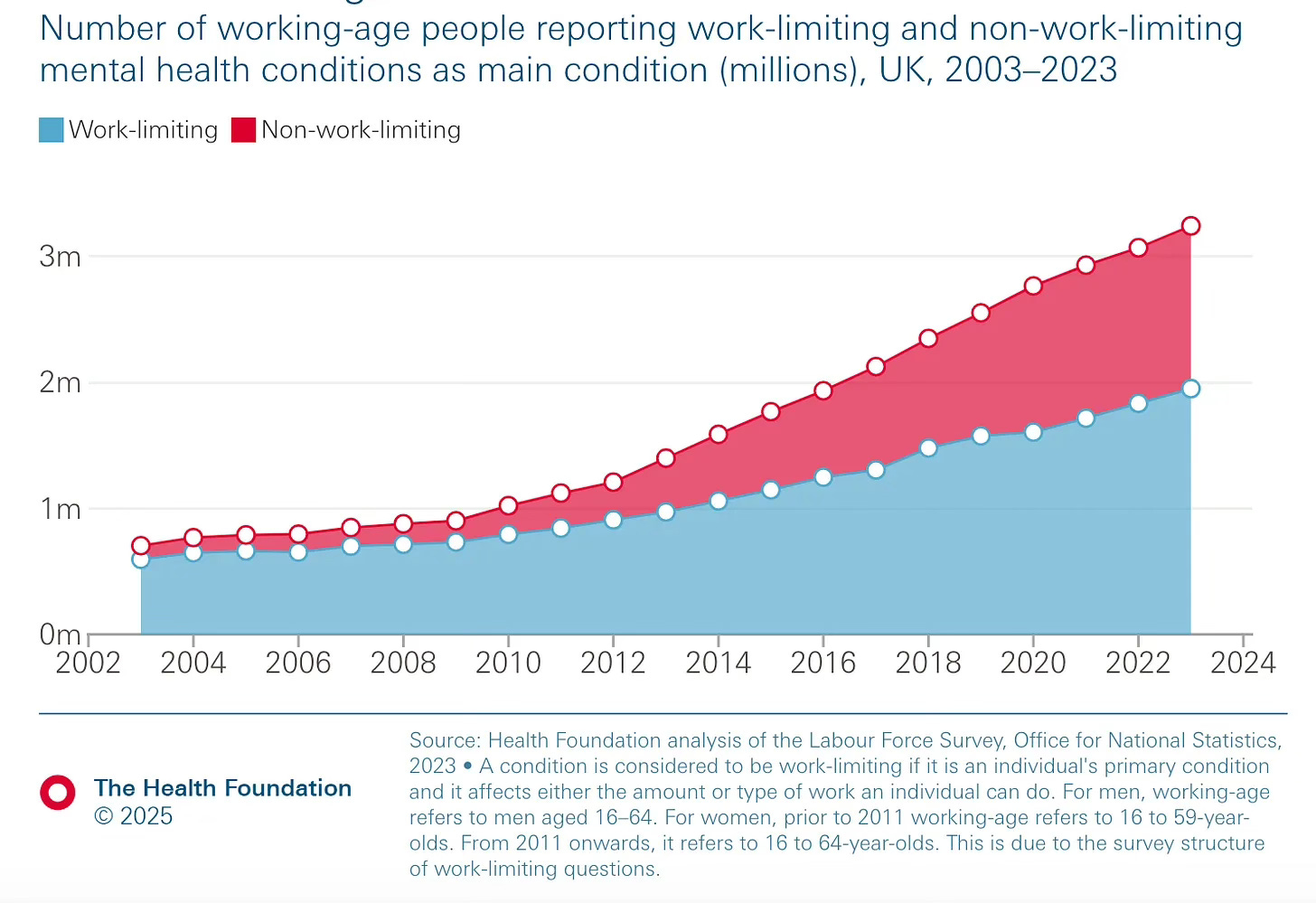

The number of people economically inactive because of long-term sickness has risen to over 2.5 million people, an increase of over 400,000 since the start of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, according to the ONS. And of these, over 1.35 million (53%) of those inactive are so because depression, bad nerves or anxiety. That is a 40% increase since 2019.

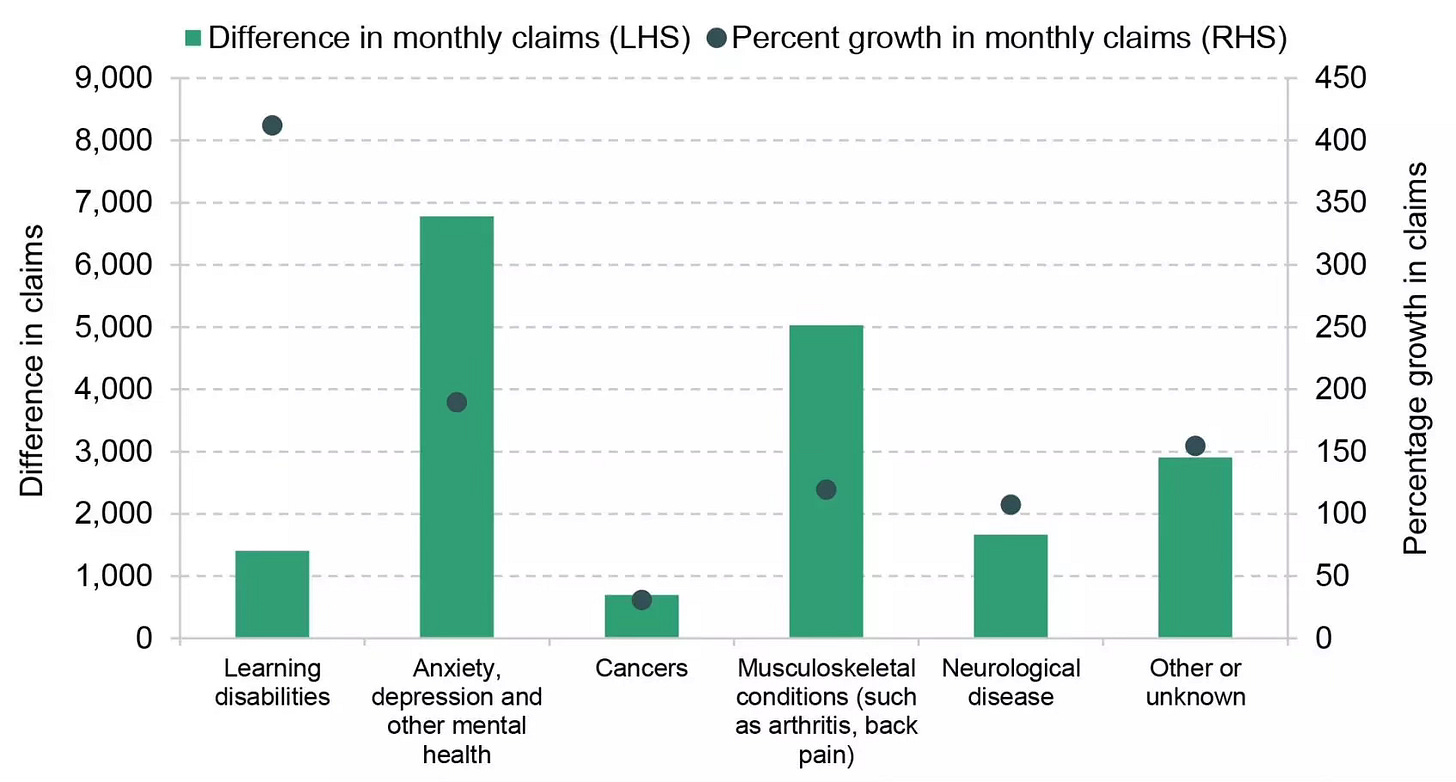

The Institute of Fiscal Studies reported on the growth and change in monthly PIP awards by condition, 2019–20 to 2023–24, with quite startling data: that there has been almost 200% growth in claims in PIP for Anxiety, depression and other mental health issues…since 2019!

But what doesn’t appear particularly clear, is either how we’ve gotten here so quickly or that, despite the massive expansion of both diagnostic capability and in the delivery of psychotherapeutic and pharmacotherapeutic remedies, we just don’t seem to be getting any….happier. More people are seeking help, more help is being delivered, but the trend lines point to ever more people seeking ever more help without end. So I think it’s apposite to ask the question, as do others, where is all this heading?

The Evidence is Telling

Whether increasing emotional awareness is a morally good or bad thing is difficult to unpack, at least for me. I’ve always believed (probably incorrectly) in the importance of the collective unit rather than (just) the individual, particularly in the emotional domain. Not being a psychiatrist or a psychologist, my views on such things are driven by my values, probably inculcated in me by my parents and with no small amount of influence from the different countries I’ve lived in and cultures I’ve benefitted from along the way. I’m probably deeply suppressed

But I believe that the collective good is the social good, and there is some value, for the individual, in feeling and believing that their contribution to it, whether or not it comes at a personal cost (emotional or otherwise), delivers some purpose in life. I want to believe that we’re not inherently selfish sentient beings - many cognitive scientists will prove me wrong - but that we see some value in being part of a group, and in working to support the mutually beneficial outcomes of that group. Case studies in the mentality of military units and indeed families, about what personal sacrifices they make for one another due to the close emotional bonds they share, is, I think, something that a close-knit society can achieve for the broader whole (more on that later).

So with that in mind, I suppose my assessment of whether this emotional awareness is a net positive or negative is what impact it has on society as a whole as well as the impact on the individual. And for that, I turn, once again, to the sterling work of

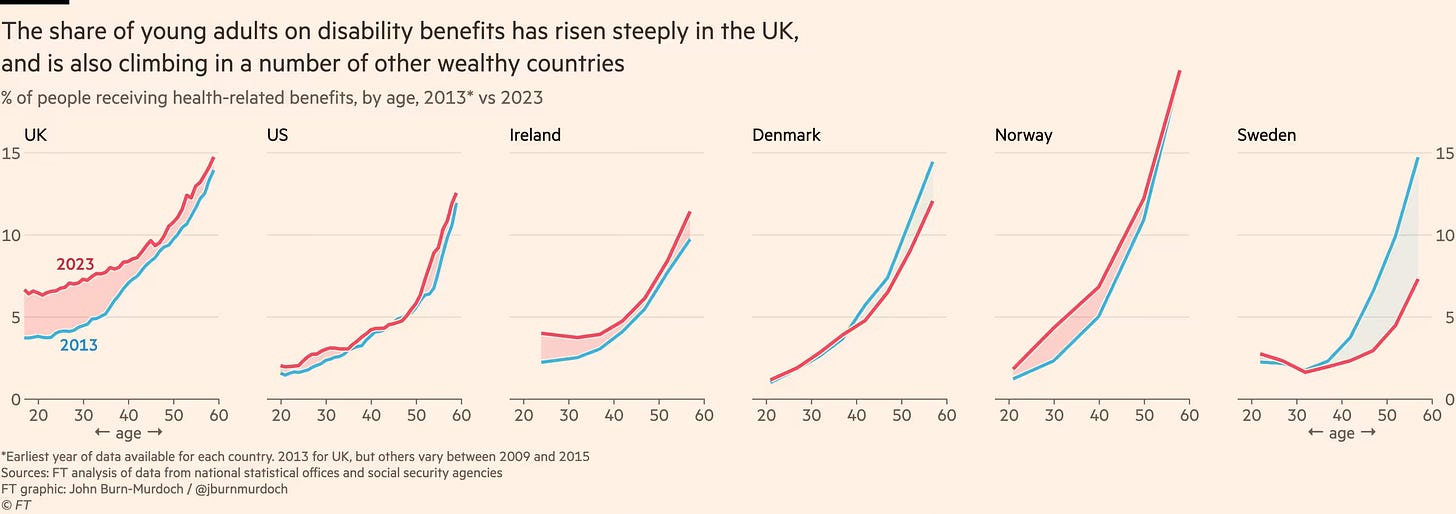

of the Financial Times, for his piece last year, entitled “Out of work and unwell: the worrying rise of young people on benefits”.This has been the meat of much of the reporting after Wes Streeting’s briefings - the economic impact of our mental health, and indeed which generations are most likely to fixate upon it. And what the charts above present is that this phenomena is by no means unique to the UK - increasing numbers of people across all age groups are “more emotionally aware”, but what is unique to the UK is that the impact is most acutely felt in the younger generation. So, in a period where national budgets and expenditures are being discussed, and what we, as a social unit, want for our country and our children’s future, I think it might be useful to interrogate what the impact might be for society as a whole.

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), spending on health-related benefits for working-age individuals in the UK increased from £36 billion in 2019–20 to £48 billion in 2023–24, with projections indicating a rise to £63 billion by 2028–29. That will be over 2.1% of GDP - for those of you who remember how much our friends across the pond wanted us to invest in defence as a percentage of GDP for NATO to be kept alive, that figure is startlingly close, and in fact probably is comparable to what we currently invest in defence. The lost tax receipts, just from those on long-term sick for mental health issues, is almost £13bn* - that’s enough to build 150 hospitals**, 650 schools***, 420 miles of new rail track (if we constructed it as efficiently as the French) which would see HS2 completed. The socio-economic cost is clearly real

Where does that leave us?

So where does all this leave us? Are people gaming the system or are they genuine in their need for support? Can both statements be equally valid at the same time?

It brings to mind the conversation I had with one lucky young pup in our local park after school one day. As a childminder for a number of the families who attend our local primary, she’s earning, in her words, “quite well”, at least to work from 1530 until 7pm Monday to Friday. And when asked what she does with the rest of her time, she happily told me she drew the dole to cover her rents so she could use her hard earned cash drinking with her friends of an evening and meet up for fun during the day.

That conversation made me think about the economic impact of not only her - someone who was clearly gaming the system - but others who make a choice not to work. I emphasise the word “choice” here - I am not, nor ever will be someone who wants to see the abolition of the welfare state (naming my son after Aneurin Bevan as I did) - because there are clearly those who really, desperately need our help and deserve our compassion, support and funds when they do. But I’m not sure this young lady qualified. And I suppose the moral question we all have to ask ourselves when feeling depressed or anxious, is whether or not those feelings we validate, act on and realise to their fullest manifestation both for ourselves and others, are sufficient a reason to place our own emotional needs above the needs of society as a whole. As Will Self put it: have we “become a society that cannot tolerate sadness, grief, or distress, where psychiatry has become the priesthood that offers absolution through prescription.”?

I sincerely hope not but fear that we are fast developing a culture in which resilience and our ability to mentally and physically push ourselves through difficult times to reap the rewards of the realisation that we can persevere is being rapidly diminished in favour of a narrative that places individual emotional validity at the expense of all. I find it as no surprise that in this landscape, the Andrew Tate’s of this world find room to manoeuvre and exploit the vulnerability of those who are looking for change. We should all of us find time and space to reflect how we can be more emotionally available and responsive to our feelings without fundamentally losing our ability to successfully navigate a path through them. Because there is, at least in my layman’s view, some value to be had in the fight. Because all of us have battles raging in us most of the time. All of us can feel the full spectrum of our emotions as intensely as the next. But the moral question for us all is whether we permit the more destructive elements of our feelings to own who we are, what we do and what we are capable of achieving. I would hope that we can all see that as a driving force to help us pull through.

With thanks for the reporters and reports who have helped me compile this drudgery…

•These figures assume 1.35 million people are economically inactive due to mental health, with an average potential salary of £30,000 and an effective tax rate of 32%

** Assuming average cost / ,2 of £4,310/m² × 20,000 m² = £86.2 million per hospital.

*** assumes £20m / school